Mohalakane, otherwise called “hardy aloe” in English, may be good for your health. “That is because it contains healthy substances called antioxidants, among other things, which reduce chances of long-term diseases,” says Khotso Mokoroane, the National University of Lesotho (NUL) student who just published an incredible research work on Mohalakane.

Mohalakane, known as “Aloiampelos striatula” among the scientists and “hardy aloe” among the English, is a famous, gentle and respected laxative.

Basotho have used it for ages to treat intestinal problems or to just refresh themselves. However, a study carried by Mokoroane has shown that there is more to this plant than meets the eye.

His work, titled, “2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging activity of extracts from Aloiampelos striatula” is published in a prestigious “Food Research” international journal.

(Join PhuthaLichaba, the future bank of the People by the NUL Innovation Hub here: www.phuthalichaba.com)

“We have found that mohalakane is rich in antioxidants,” Mokoroane said.

What are antioxidants?

We will make sure that we put this strange work in a layman’s language, at least we will try. Demystifying science is what we are paid for.

Antioxidants are compounds that prevent oxidation. O.K… But what is oxidation? It is a chemical reaction that can produce free radicals, thereby leading to chain reactions that may damage cells of living things. In the last sentence, focus only on this phrase “…that may damage cells…” and ignore the rest.

From the above paragraph, we learn that Mohalakane has substances called antioxidants which prevent oxidation, a process that may damage your body cells, making you sick. In fact, the word antioxidant means “against oxidation.” “At its worst, oxidation can cause cancer among a host of other diseases,” Mokoroane said.

So what antioxidants did Mokoroane find in his study?

Before we answer that question, it is okay to note that he also found other substances and here is a list of what he found: phytochemicals called tannins, phenolic acids, sterols, tri-terpenoids and alkaloids. Never mind the fancy names.

He also found nutrients such as amino acids, proteins and sugars.

You probably noted two strange chemicals there: tannins and phenolic acids.

Ya! Those chemicals are antioxidants.

“The moment we noted the presence of those two chemicals when we were analysing mohalakane, we immediately gave an almost exclusive attention to them,” Mokoroane said. We wanted to test their abilities as antioxidants.

This is the point where it gets more interesting.

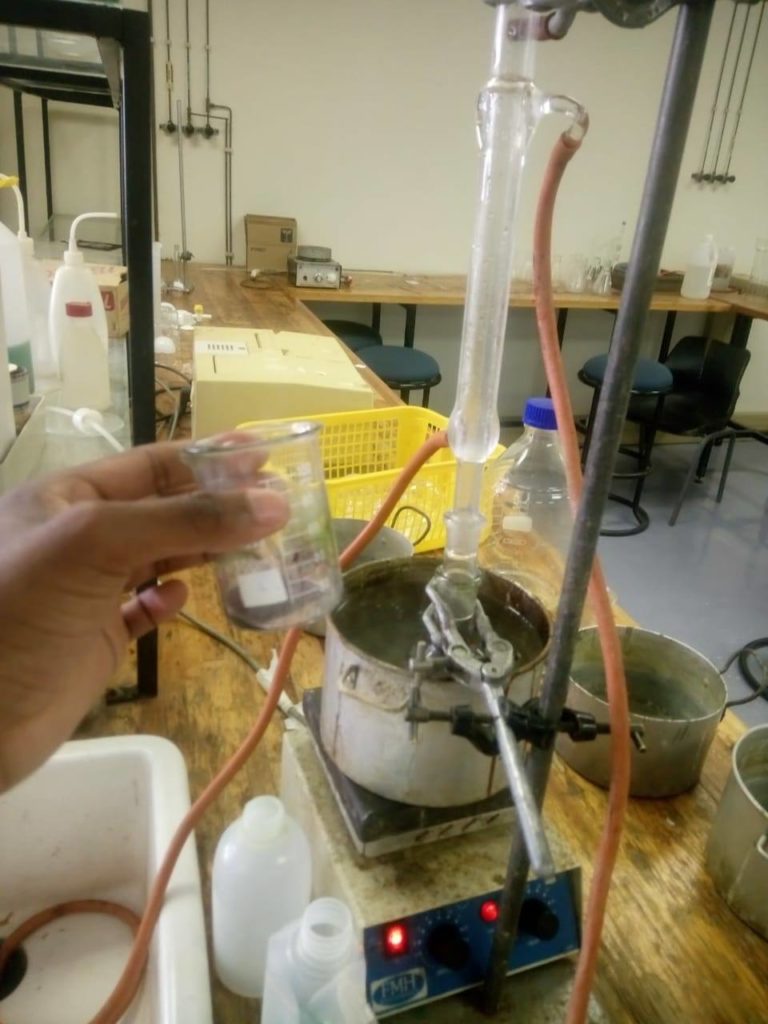

So they conducted antioxidant tests on solutions that contained tannins and phenolic acids from mohalakane.

“We used two methods, one based on Ferricyanide Reducing Assay Power and another based on DPPH Radical Scavenging Power,” he said effortlessly for a guy who has spent the last four years studying the mysteries and secrecies of Chemistry and Chemical Technology.

Well, our job is to demystify Chemistry today and we hope we are doing a good job, at least up to this point.

Let’s make an example with Ferricyanide Reducing Assay Power—time won’t allow us to move to DPPH Radical Scavenging Power, although we would love to.

Time is enemy— “nako ke sera.”

But before that, let’s think about what we are trying to get at.

Compounds—like those found in our bodies—can sometimes loose electrons. Yep! Most of you have, at minimum, heard about this in high school. In High school Chemistry, “sirs” and “ma’ams” taught us that when a compound or an element lost electrons, it got charged, which made it ready to take part in a reaction so that it satisfies itself.

In some cases, when an element or a compound has lost its electrons, it is then called a “free radical.”

Put simply, a free radical is like a single man who goes around aggressively looking for a wife after losing his. He is willing to cause trouble to another married man by taking his wife—leaving that man himself a dangerous free radical who will attack another nearby family to regain a wife. Left unchecked in your body, free radicals break up compounds to pull electrons from them, and the broken compounds themselves revenge on the nearest ones in a chain process scientists call “chain reaction.”

—yes, Lifaqane (Mfecane) can happen in your body.

So how would you stop Lifaqane in your body?

You would want to make sure that you give unmarried women (uncommitted electrons) to the free radicals so they don’t go around upsetting stable families.

In this experiment, Mokoroane chose Ferricyanide to represent real-life free radicals in your body. Although it is not a radical itself, ferricyanide, like radicals, can pick electrons from other compounds.

“In those experiments, we were able to give Ferricyanide some electrons from Mohalakane’s antioxidants, turning it into Ferrocyanide—its new name after receiving electrons.” “We checked through photo-spectroscopy that Ferricynide changed into Ferrocyanide as it received those electrons from the antioxidants.”

That proved mohalakane indeed had antioxidants.

Those with a bit of chemistry will appreciate the following wedding: [Fe(CN)6]3− + e− ⇌ [Fe(CN)6]4−. Don’t worry if you missed this wedding, you can survive without it. There is no probably no ferricyande in your body. But there may be ferricyanide-like war-loving free radicals which may either destroy your cells looking for electrons—wives—or be satisfied by electrons donated by Mohalakane’s antioxidants.

(Join PhuthaLichaba, the future bank of the People by NUL Innovation Hub here: www.phuthalichaba.com)